While not as prolific as they were just a few years ago, the Rams under offensive coordinator and head coach Mike Martz were maybe the best passing offense of all time. They set a gazillion scoring and passing records, and now teams like the Chiefs and Cardinals run their offense verbatim and others like the Bengals run extremely similar schemes. The offense itself goes way back to the Don Coryell and Sid Gillman days, as interpreted by guys like Ernie Zampese and Norv Turner.

The vertical passing game is well documented and very important (in fact they run the 3-vertical I link to in the previous post), but the shallow cross has been a great tool for them to hit passes underneath the fast dropping linebackers and to get good matchups with speed receivers getting rubs and running away from man to man for big play potential.

The Rams integrate the shallow cross into four main concepts: drive/cross-in combo (same side), hi-lo (shallow/in opposite sides), mesh, and the choice.

Running the Route

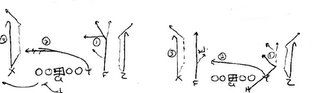

The route is designed to be run at a depth of 5-6 yards. It is mandatory that it at least crosses the center, and often can be caught on the opposite side of the field (in fact many pro-teams use the shallow as a way to attack and control the opposite flats). Here is the route shown vs. both man and zone and some coaching points:

1. First step is directly upfield. Vs. press man stutter step and get inside position.

2. Rub underneath any playside receivers inside of you.

3. Initially aim for the heels of the defensive linemen

4. Cross center. Aim for 5-6 yards on opposite hash.

5. Read man or zone (described below)

6. Vs. zone settle in window facing QB past the center-line (usually past the tackle). Get shoulders square to QB, catch the ball and get directly upfield.

7. Vs. man staircase the route (shown above, push upfield a step or two) and then break flat across again and keep running. No staircasing when running mesh.

Reading man or zone: After your initial step, eye the defenders on the opposite side of the centerline. Two questions: who are they looking at? and what does their drop look like?

If they are looking at the receivers releasing to their side and turning their shoulders to run with those receivers, it is probably man (on mesh look if they are following the opposite receiver).

If they are dropping back square and looking at either the QB or at you, it is probably zone. Expect to settle. Even if it is zone and there is nothing but open space, keep running; we'd rather hit a moving receiver than a stationary one.

Now, onto the concepts themselves.

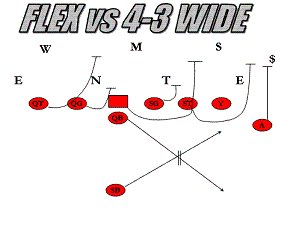

Drive/Shallow-in

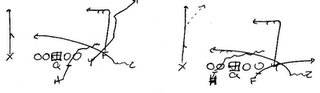

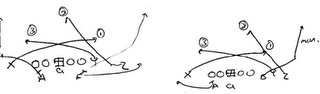

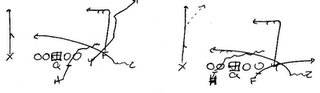

The first is the "drive" concept, as taught in the west coast offense. You can find a great article on the classic form of the play common to west coast offense teams here. Here is a diagram below:

This is the most versatile of all the shallow-cross routes, and my personal favorite. The in route is run at 14-15 yards (can shorten to 10-12 for H.S.) and the corner is a 14 yard route (can also be shortened to 10-12).

The Rams typically use two different reads on the play, depending if it is man or zone. Against man the read is shallow->in->corner (RB dump off). Against zone it is a hi-lo: corner (or wheel), in, to shallow.

The shallow and sometimes a quick flat are good options built in against blitz, and the play can be run from many formations, including the bunch.

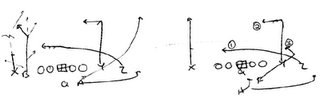

Below are some variants. On the right, is incorporating an angle route into the play, and it always gets read inside to out. On the left, the play is run from a balanced one-back set, and the backside can have almost any two-man combination used. Below the smash is shown, but it could be curl/flat, out/seam, post-curl, or any other combination. Typically a pre-snap or post-snap determination can be made based on man/zone or whether the coverage rotates strong.

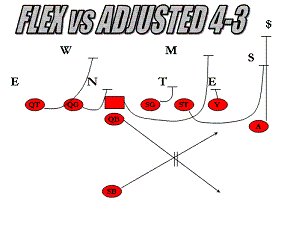

Hi/Lo

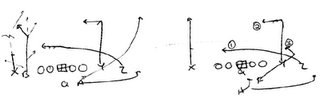

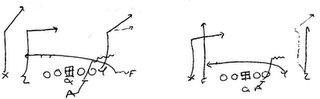

The hi/lo shallow concepts is similar to how Texas Tech/Mike Leach and the other Airraid gurus run their shallow series. For more info, try the link. Below is what the Rams do.

The in route is at 15 yards as is the post route. Both can be shortened to 10-12 for lower levels. The frontside corner is run at 15 and is only thrown vs. certain man looks.

The base read is in->shallow->RB dump-off. (As a footnote, Texas Tech reads it always shallow->in->RB. I think this is probably the better read for lower levels QBs, since it ensures they will get the ball off quickly and get a sure completion, only throwing the route over the middle when the defenders maul/jump the shallow.)

Also, versus quarters coverage the Rams like to look through the In to the Post route. The idea is that if the safety jumps the In they can hit the post up top behind him. Typically the weak safety (to in/post side) is watched on the early part of the drop, and if he comes up for whatever reason (probably to cover when a blitz is on!) the post becomes the #1 read.

The pass on the right is read the exact same, just some of the responsibilities are switched.

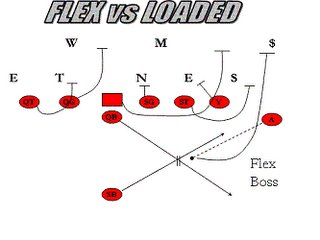

Mesh

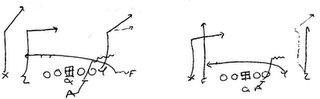

The mesh route has extensive literature and discussion on it and the intricasies of the meshing receivers can be found elsewhere. The basic gist is that two receivers cross over the middle getting a rub, which is very effective versus man. Sometimes it also can be a horizontal stretch against zones with four underneath men. Martz has adjusted the play so instead of a frontside corner hi/lo read or even a post to take the top off like Norm Chow likes, he has the Z receiver running a curl at 12 yards over the center. What happens then is it floods the underneath zones with four defenders to cover five receivers, just like on all-curl. So it is a very effective man and zone play. Also, almost always at least one of the two receivers threatening the flats will run a wheel route, giving a deep option.

The QB will get a pre-snap read for the wheel route, basically checking to see if a LB has him in man and/or if the deep defender to that side might squeeze down with no immediate deep threat. The read is then right to left, X-Z-Y, or shallow, in, shallow. Again, as before, the shallows will look to settle vs. zone but they need to get a little wider here. Also, as explained elsewhere for the mesh the Y sets the top of the mesh at 6 yards and X comes underneath at 5. It is best if they can cross going full speed, but must navigate the LBs and undercoverage (and the ref!). If all is covered vs. zone the ball can be dropped off to the flat to the RB or tight end/H-back.

Choice

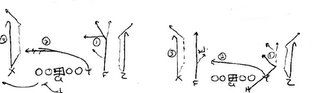

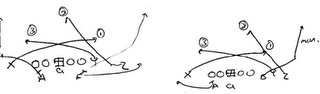

The Rams call the play with numbers and will tag either the post/middle read or the shallow so I'm not sure what they call it, but the play is adapted from the old run and shoot choice route. The choice route has been successful for teams for years, and the Rams are only happy to incorporate its concepts.

However, while the choice is typically read from the single receiver side over, the Rams read it opposite, with the single receiver side the late read and the middle-read the primary. The play is really intended as a spring to a slot receiver or RB in the seam with the ability to read on the fly.

They change the reads up for the post/seam pattern here run by F and H, but essentially it is similar to the middle read on the 3-vertical play, where he reads MOFO or MOFC and looks to attack the deep middle against open coverage and break flat across underneath a deep middle safety. The Rams also give him the option to break it off against blitzes and, in the case of getting H out in the second diagram, versus "wide" coverage (i.e. a LB squatting outside waiting for him to go to the flat) he can stick it at the LOS or just beyond and run an angle back inside (it helps to have Marshall Faulk!).

The read is post-read->shallow->comeback/flat read. So if they squeeze the post-read the shallow is next and then the QB works the comeback and the flat off a hi/lo read. In the second diagram the seam just clears out or breaks off his route if there is a blitz.

I suggest against having hot reads and sight adjustments to both sides combined with a multi-direction read route unless you are the St. Louis Rams. It is still an excellent play if you keep at least 6 in to block and let the shallow be the hot read, or you can even run it as a 7 man protection if you take away the backside comeback route.

Conclusion

That's a brief overview of the various ways they go about it and the reads. A HS team needs one, maybe two ways of doing this. Lots of teams have been successful using some of these. Florida State won a championship and Charlie Ward a Heisman trophy running the drive version, where if the D dropped off and covered the shallow, swing, and curl, he ran a draw. All of these are high percentage throws. Remember: speed in space! It's a motto that scores points and wins games.

The vertical passing game is well documented and very important (in fact they run the 3-vertical I link to in the previous post), but the shallow cross has been a great tool for them to hit passes underneath the fast dropping linebackers and to get good matchups with speed receivers getting rubs and running away from man to man for big play potential.

The Rams integrate the shallow cross into four main concepts: drive/cross-in combo (same side), hi-lo (shallow/in opposite sides), mesh, and the choice.

Running the Route

The route is designed to be run at a depth of 5-6 yards. It is mandatory that it at least crosses the center, and often can be caught on the opposite side of the field (in fact many pro-teams use the shallow as a way to attack and control the opposite flats). Here is the route shown vs. both man and zone and some coaching points:

1. First step is directly upfield. Vs. press man stutter step and get inside position.

2. Rub underneath any playside receivers inside of you.

3. Initially aim for the heels of the defensive linemen

4. Cross center. Aim for 5-6 yards on opposite hash.

5. Read man or zone (described below)

6. Vs. zone settle in window facing QB past the center-line (usually past the tackle). Get shoulders square to QB, catch the ball and get directly upfield.

7. Vs. man staircase the route (shown above, push upfield a step or two) and then break flat across again and keep running. No staircasing when running mesh.

Reading man or zone: After your initial step, eye the defenders on the opposite side of the centerline. Two questions: who are they looking at? and what does their drop look like?

If they are looking at the receivers releasing to their side and turning their shoulders to run with those receivers, it is probably man (on mesh look if they are following the opposite receiver).

If they are dropping back square and looking at either the QB or at you, it is probably zone. Expect to settle. Even if it is zone and there is nothing but open space, keep running; we'd rather hit a moving receiver than a stationary one.

Now, onto the concepts themselves.

Drive/Shallow-in

The first is the "drive" concept, as taught in the west coast offense. You can find a great article on the classic form of the play common to west coast offense teams here. Here is a diagram below:

This is the most versatile of all the shallow-cross routes, and my personal favorite. The in route is run at 14-15 yards (can shorten to 10-12 for H.S.) and the corner is a 14 yard route (can also be shortened to 10-12).

The Rams typically use two different reads on the play, depending if it is man or zone. Against man the read is shallow->in->corner (RB dump off). Against zone it is a hi-lo: corner (or wheel), in, to shallow.

The shallow and sometimes a quick flat are good options built in against blitz, and the play can be run from many formations, including the bunch.

Below are some variants. On the right, is incorporating an angle route into the play, and it always gets read inside to out. On the left, the play is run from a balanced one-back set, and the backside can have almost any two-man combination used. Below the smash is shown, but it could be curl/flat, out/seam, post-curl, or any other combination. Typically a pre-snap or post-snap determination can be made based on man/zone or whether the coverage rotates strong.

Hi/Lo

The hi/lo shallow concepts is similar to how Texas Tech/Mike Leach and the other Airraid gurus run their shallow series. For more info, try the link. Below is what the Rams do.

The in route is at 15 yards as is the post route. Both can be shortened to 10-12 for lower levels. The frontside corner is run at 15 and is only thrown vs. certain man looks.

The base read is in->shallow->RB dump-off. (As a footnote, Texas Tech reads it always shallow->in->RB. I think this is probably the better read for lower levels QBs, since it ensures they will get the ball off quickly and get a sure completion, only throwing the route over the middle when the defenders maul/jump the shallow.)

Also, versus quarters coverage the Rams like to look through the In to the Post route. The idea is that if the safety jumps the In they can hit the post up top behind him. Typically the weak safety (to in/post side) is watched on the early part of the drop, and if he comes up for whatever reason (probably to cover when a blitz is on!) the post becomes the #1 read.

The pass on the right is read the exact same, just some of the responsibilities are switched.

Mesh

The mesh route has extensive literature and discussion on it and the intricasies of the meshing receivers can be found elsewhere. The basic gist is that two receivers cross over the middle getting a rub, which is very effective versus man. Sometimes it also can be a horizontal stretch against zones with four underneath men. Martz has adjusted the play so instead of a frontside corner hi/lo read or even a post to take the top off like Norm Chow likes, he has the Z receiver running a curl at 12 yards over the center. What happens then is it floods the underneath zones with four defenders to cover five receivers, just like on all-curl. So it is a very effective man and zone play. Also, almost always at least one of the two receivers threatening the flats will run a wheel route, giving a deep option.

The QB will get a pre-snap read for the wheel route, basically checking to see if a LB has him in man and/or if the deep defender to that side might squeeze down with no immediate deep threat. The read is then right to left, X-Z-Y, or shallow, in, shallow. Again, as before, the shallows will look to settle vs. zone but they need to get a little wider here. Also, as explained elsewhere for the mesh the Y sets the top of the mesh at 6 yards and X comes underneath at 5. It is best if they can cross going full speed, but must navigate the LBs and undercoverage (and the ref!). If all is covered vs. zone the ball can be dropped off to the flat to the RB or tight end/H-back.

Choice

The Rams call the play with numbers and will tag either the post/middle read or the shallow so I'm not sure what they call it, but the play is adapted from the old run and shoot choice route. The choice route has been successful for teams for years, and the Rams are only happy to incorporate its concepts.

However, while the choice is typically read from the single receiver side over, the Rams read it opposite, with the single receiver side the late read and the middle-read the primary. The play is really intended as a spring to a slot receiver or RB in the seam with the ability to read on the fly.

They change the reads up for the post/seam pattern here run by F and H, but essentially it is similar to the middle read on the 3-vertical play, where he reads MOFO or MOFC and looks to attack the deep middle against open coverage and break flat across underneath a deep middle safety. The Rams also give him the option to break it off against blitzes and, in the case of getting H out in the second diagram, versus "wide" coverage (i.e. a LB squatting outside waiting for him to go to the flat) he can stick it at the LOS or just beyond and run an angle back inside (it helps to have Marshall Faulk!).

The read is post-read->shallow->comeback/flat read. So if they squeeze the post-read the shallow is next and then the QB works the comeback and the flat off a hi/lo read. In the second diagram the seam just clears out or breaks off his route if there is a blitz.

I suggest against having hot reads and sight adjustments to both sides combined with a multi-direction read route unless you are the St. Louis Rams. It is still an excellent play if you keep at least 6 in to block and let the shallow be the hot read, or you can even run it as a 7 man protection if you take away the backside comeback route.

Conclusion

That's a brief overview of the various ways they go about it and the reads. A HS team needs one, maybe two ways of doing this. Lots of teams have been successful using some of these. Florida State won a championship and Charlie Ward a Heisman trophy running the drive version, where if the D dropped off and covered the shallow, swing, and curl, he ran a draw. All of these are high percentage throws. Remember: speed in space! It's a motto that scores points and wins games.